Improving land tenure security in informal settlements of Nairobi: The journey continues

The Chairperson at Mashimoni settlement, Mr. Dennis Isenya displays the 2017 settlement plan

The Chairperson at Mashimoni settlement, Mr. Dennis Isenya displays the 2017 settlement plan

In a guided interaction with the community members, the delegation from GLTN learned about the ongoing community-led processes in the fight for secure land tenure and housing, including updating the community data which has greatly contributed to anti-eviction campaigns (the settlements have been able to block numerous forced eviction attempts based on the generated data), engaging in community savings schemes, lobbying for improved basic services in the settlements, as well as training on the provisions of the Community Land Act (CLA) of 2016. During the discussions, the slogans “Umoja, Nguvu Yetu”, “Ardhi na Makao, Haki Yetu”, “Uoga, Umaskini Milele” translated as “Unity, Our Strength”, “Land and Housing, Our Right” “Fear, Poverty Forever” among others, were chanted by the community as they explained with great enthusiasm their processes, including the history of the settlements, milestones, challenges, and the vision for the settlements. The community in Mashimoni and Mabatini have embraced the community approach with regards to seeking tenure security for their land, considering the contested land issues therein, and are working with Pamoja Trust and other likeminded civil society organizations towards building their capacity to understand and utilize the provisions of the CLA in relation to this venture. A key element in the CLA is that ‘community’ is liberally defined to allow for “a consciously distinct or organized group of users of community land, who are citizens of Kenya and share any of the following attributes: common ancestry, similar culture or unique mode of livelihood, socio-economic or other similar common interest, geographical space, ecological space or ethnicity” (CLA s. 2). The definition of ‘community’ under the CLA is progressive, in that the definition of “community” accommodates persons living in urban areas/informal settlements (and not only those living in rural areas as it was historically) who aspire to take on a collective approach to registering their land. Currently, capacity building on the is ongoing to promote understanding of the attendant rules and regulations on the part of the community as outlined in the Community Land Regulations of 2018 which aim at operationalizing the Act, with respect to, among other things, recognition, protection and registration of community land rights, community land management committees, registration of communities, conversion of community land, settlement of disputes relating to community land, conversion of group representatives, etc.

John Gitau of GLTN addresses the meeting during the monitoring mission

John Gitau of GLTN addresses the meeting during the monitoring mission

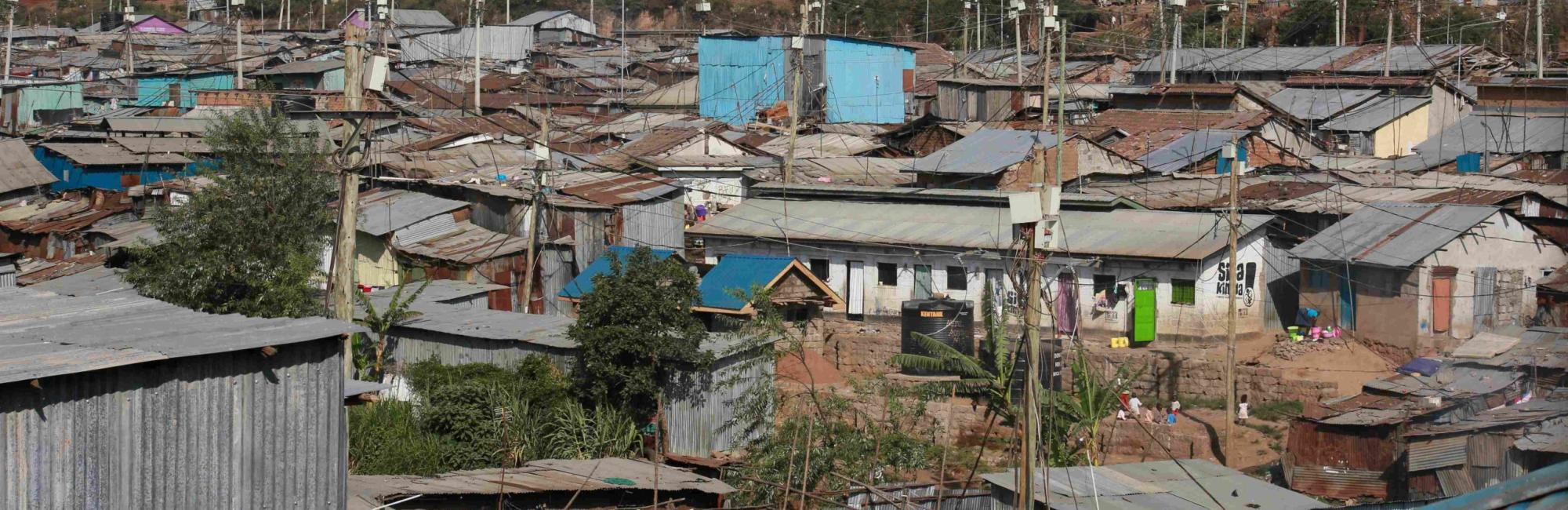

The mission also included a short walk within the settlements, a landscape characterized by hundreds of structures laid haphazardly without clear structural or spatial planning. Majority of the housing in Mathare is comprised of rental properties, including high-rise tenements, owned, and managed by a few individuals. In both settlements, it was revealed that there exist spatial plans (Mashimoni-2017, Mabatini-2012) based on the previous collection of community data, which are yet to be implemented, but which also need to be updated. In Mashimoni, the community is organizing itself to continue pursuing allocation of their land from the Kenya Defence Force (owner of the land) by engaging the KDF and other relevant authorities including the Nairobi County Government and the National Land Commission on this issue. For Mabatini, a judgement by the Environment and Land Court (Nairobi) in 2021was passed in favour of the community where allocation to a private developer was revoked. The Court further ruled that the land should be allocated to the residents of Mathare Mabatini village on a communal basis. This is a huge win for the Mabatini community and has provided an opportunity to pursue collective ownership of the land under the CLA. This far, community efforts in both Mabatini and Mashimoni towards securing their tenure rights are encouraging. However, they cannot be able to do it alone and aside from the third sector, there is need for the government to provide an enabling environment for land tenure regularization, for example by improving the basic services to make the settlements liveable neighbourhoods, lessening the bureaucracy in government offices regarding the pursuit of these lands, and supporting incremental planning in a cost-effective manner towards enabling security of tenure on the same land (in situ), in time.